COVID-19, Incarcerated People, and Their Loved Ones

March 2020 changed the U.S. and nations across the globe as Coronavirus spread rapidly. As described by the Center for Disease Control, Coronavirus (COVID-19) is an illness caused

by a virus that can spread from person

to person. The symptoms can range from mild

(or no symptoms) to severe (death).

One of the forgotten populations at higher risk for exposure is incarcerated individuals and correctional staff. Prisons are now effectively locked down in attempts to limit movement and exposure.

The conditions in jails and prisons are not conducive to preventing the spread of coronavirus. Social distancing is nearly impossible. The average cell size is 6' by 8'. Often, cells are shared with at least two people. Some institutions use dorm-style "cells" where there is a large open concrete building with bunks separated by 4-5ft dividers. Bunks are camp-style, one right above the other. How can anyone be expected to keep a 6-foot distance from one another in such conditions?

Beyond the structural barriers to social distancing, other policies and rules may also impede efforts to contain the virus. For example, hand sanitizer is considered contraband in facilities across the U.S. due to its alcohol content. Accordingly, incarcerated people are not able to have access to it. Some facilities have begun to allow access to hand sanitizer, but a large number have not.

Due to conditions ripe for close contact and lack of access to personal hygiene products and protective equipment, the U.S. is confronted with distinct ramifications for incarcerated people. As the world leader in incarceration, with the highest national incarceration rate, the consequences for our nation are immense. Equal Justice Initiative indicated, "Nationwide, the known infection rate for Covid-19 in jails and prisons is about 2½ times higher than in the general population.

Notably, as shown by Covid Prison Data, more incarcerated people have tested positive for COVID-19 in comparison to correctional staff.

As documented by The Marshall Project, there is significant variation in cases across states. As of May 8, 2020, Ohio has the highest number of COVID-19 cases at 4,321. Kansas has the eighth highest number of cases at 615.

As depicted in this map created by Covid Prison Data, Kansas has one of the highest percentages of incarcerated people confirmed positive as of May 12, 2020.

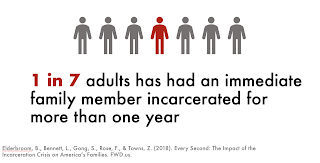

Another concern is the lack of information provided to families of incarcerated persons. Beyond the 2.3 million people incarcerated in the U.S., they leave behind a family system on the outside. A recent study indicated approximately half of the U.S. population has had a family member incarcerated at least one night. And, one in seven adults has had a family member incarcerated at least 1 year. Notably, the rate of familial incarceration is amplified among Black adults.

Already, having a loved one incarcerated is a stressful experience. I can speak from my own lived experience having incarcerated parents throughout my childhood and young adulthood. Having a loved one incarcerated during a pandemic is a nightmare to say the least. An article about facilities in Indiana suggested families were not being consulted on the conditions of their loved ones. The article states, "Families say prisons refuse to disclose basic information that would put them at ease, including whether [their loved one] is alive. In some cases, families didn’t know their loved ones were sick until after they had died."

One of my students sent me a Facebook post with a video taken by a man incarcerated in Lansing prison by a cell phone (contraband). The video expressed the incarcerated men's concerns with a lack of social distancing and being housed near the infirmary where those diagnosed with COVID-19 were being treated. The incarcerated individuals started an uprising to protest the conditions.

The truth is, we don't exactly know how incarcerated people are being protected during the pandemic and what impact this historical tragedy is having on their loved ones on the outside. It is, for this reason, I am currently conducting a mixed-methods study (surveys and interviews) with loved ones of incarcerated persons. My hope is by gaining information from loved ones of those incarcerated, it will provide more detailed information into how incarcerated people are being protected, what procedures are in place for testing and treatment, how the pandemic has impacted communication among families, and how the pandemic is impacting the well-being of incarcerated people and their loved ones.

In the meantime, here are my recommendations to address COVID-19 among incarcerated populations:

1) Reduce incarcerated populations by releasing low-risk individuals and those near the end of their sentences

2) Enact widespread testing of incarcerated people and staff

3) Engage in continuous cleaning and sanitation

4) Provide personal protective equipment (i.e, masks, gloves) for incarcerated people and staff

5) Allow social distancing when possible and ensure social distancing for vulnerable individuals

6) Keep families informed of general policies and specific updates about their loved ones

7) Do not allow staff or others to enter the prison with symptoms and mandate paid medical leave

The CDC released a detailed list of operational recommendations specifically for correctional facilities.

Comments

Post a Comment